The Hair, the Faith, And the Law: When Dreadlocks Become Evidence of Devotion

“No razor shall touch his head, for the locks of his hair are holy unto the Lord.”

14 Nov, 2025

Share

Save

In a small correctional facility in Louisiana, USA, a Rastafarian named Damon Landor sat as a living testimony of faith. For nearly twenty years, he had carried his dreadlocks like commandments—strands of covenant between man and Jah.

Then came the day of violation. Guards, claiming routine procedure, seized him, pressed his head down, and with mechanical indifference, sheared off his locks.

Not merely hair—but history.

Not fashion—but faith

Not strands—but scripture.

In that moment, the scissors did not just cut hair; they severed belief.

Landor rose to sue. He didn’t sue for vanity; he sued for sanctity—under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalised Persons Act (RLUIPA)—arguing that his forced haircut was not discipline but desecration.

The question that reached the U.S. Supreme Court was chillingly simple:

“Can a man whose faith has been forcibly shorn seek compensation?”

The Jurisprudence of Hair

To the unthinking world, hair is cosmetic. But to the Rastafarian, it is cosmic—a theology growing in follicles. It is the visible manuscript of an invisible covenant—a declaration that the body itself can be scripture.

In biblical cadence, Numbers 6:5 proclaims:

“No razor shall touch his head, for the locks of his hair are holy unto the Lord.”

Thus, when a guard, schoolteacher, or police officer forcibly cuts a Rastafarian’s hair, it is not grooming—it is grieving.

It is not discipline—it is desecration.

It is not hygiene—it is heresy.

Every cut becomes a sermon of oppression. Every fallen strand is a silent testimony of pain.

The Washington Revelation

Across the continent, in the progressive chambers of Washington State, the law has learnt what culture refused to.

It has written into its labour code a modern psalm called the CROWN Act—Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair.

In that statute, dreadlocks are no longer merely a style; they are a protected form of identity.

To discriminate against them is to discriminate against history, race, and belief itself.

This Act tells employers:

“You may own the contract, but not the crown.”

For in the hierarchy of human dignity, hair that grows as God designed is not a liability—it is liberty.

Uganda in the Mirror

Now, let us turn homeward—to Uganda, where dreadlocks still walk like suspects. Here, a man with locks is not presumed religious—he is presumed rogue. A woman with natural hair is told she’s unkempt, unprofessional, and “not corporate enough.”

The unspoken policy of prejudice persists:

“Neatness is whiteness, faith is foreignness, and conformity is currency.”

But under the Constitution of Uganda, freedom of religion and the dignity of a person are not selective privileges—they are universal guarantees.

Article 29 protects freedom of conscience and belief.

Article 24 protects from inhuman and degrading treatment.

Article 21 outlaws discrimination in all its guises.

When the state or an institution cuts a Rastafarian’s hair, it is not merely violating grooming codes—it is performing a constitutional amputation. It trims not just the scalp but the soul.

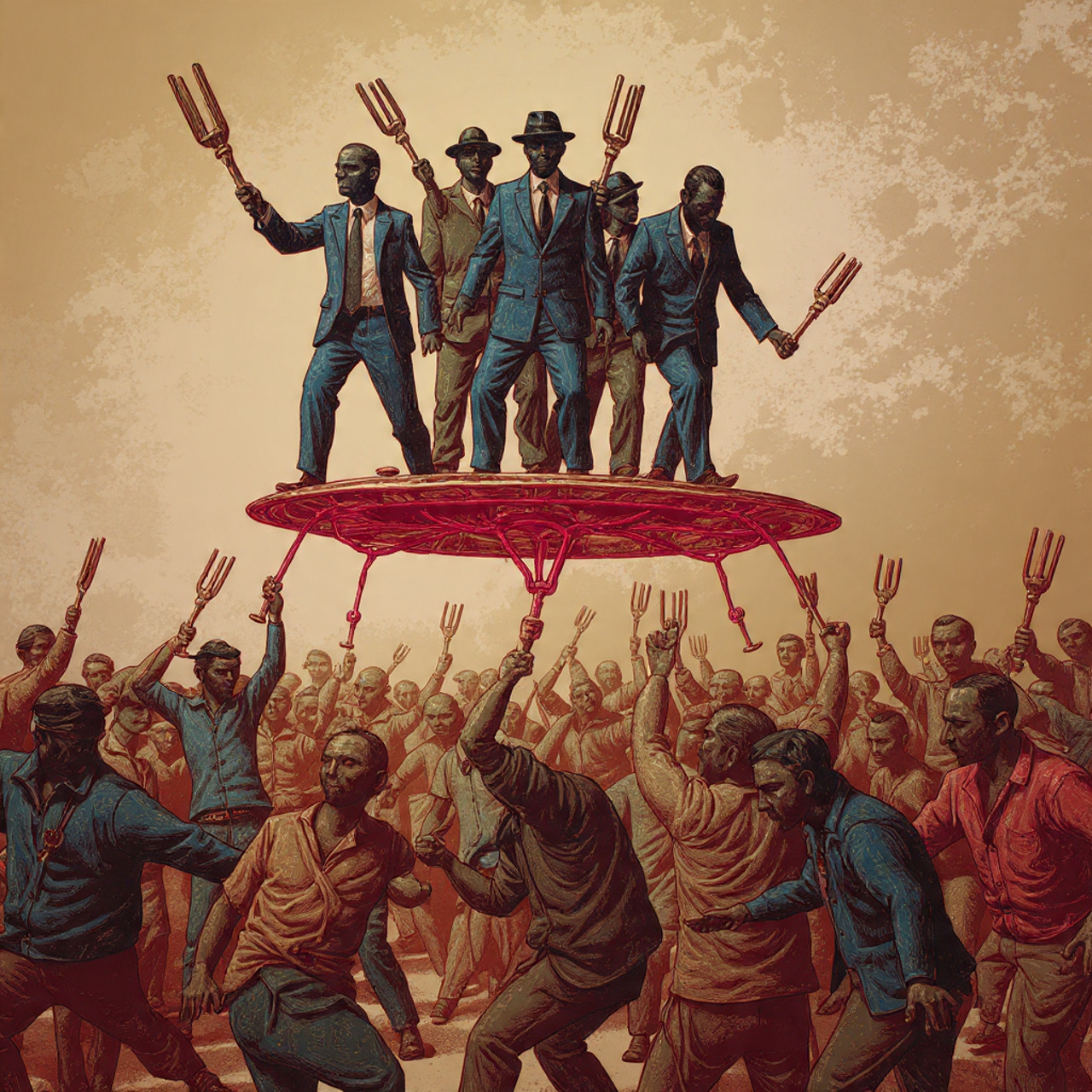

The Politics of the Razor: The Case of Eddie Mutwe

Let us descend from abstraction into blood and history—into Uganda’s own theatre of scissors.

When Eddie Mutwe, bodyguard to opposition leader Bobi Wine, was arrested and his beard forcibly shaved, the act was more than punitive.

It was political surgery—a message that resistance must be stripped not only of its slogans but also of its symbols.

To shave him was not grooming—it was silencing.

It was a declaration that the state can still humiliate to discipline, still desecrate to dominate.

In that moment, the barber’s hand became an instrument of the regime; the clipper became a weapon of conformity.

The state had turned into a barber of belief.

If hair is an extension of identity, then Eddie Mutwe’s shaving was an assault on religious freedom, dignity, and personhood.

It was the Ugandan equivalent of the Landor case—a collision between the sacred and the sovereign, between faith and the fist.

The Legal Architecture of Faith and Follicle

Under Uganda’s Constitution, Mutwe could invoke:

Article 29—Freedom of religion and belief.

Article 24—Protection from cruel or degrading treatment.

Article 21—Equality and freedom from discrimination.

Article 50—Right to seek redress for violation of fundamental rights.

Article 44(a)—Non-derogable right to be free from torture or degrading treatment, even during emergencies.

Precedents like Attorney General v. Susan Kigula & 417 Others (2009) and Salvatori Abuki v. Attorney General (1997) affirm the sanctity of human dignity and freedom from cruel acts.

Thus, if Eddie Mutwe sought constitutional redress, he could demand:

A declaration that the act of shaving was unconstitutional and degrading.

Damages—general and aggravated—for humiliation, spiritual injury, and breach of dignity.

Institutional reform orders compelling police and prison services to respect religious appearance in custody.

This would not just be compensation for hair but for the humiliation of faith.

The Case for Compensation

Can a man sue for that?

Yes. He must.

He must not sue for vanity but for vindication.

For in the legal imagination, compensation is not about money—it is about moral accounting.

It is society’s way of saying:

“What we broke, we acknowledge; what we humiliated, we restore.”

Ugandan courts must begin to recognise appearance as theology—to see dreadlocks not as rebellion but as revelation.

They must understand that bodily integrity includes the right to define what sanctity looks like.

A successful suit for a forced haircut would open new jurisprudential frontiers—signalling that the Constitution is not aesthetic-neutral but faith-sensitive.

The Theology of the Follicle

Every society must decide what its scissors mean.

In barbaric hands, they are weapons of conformity.

In enlightened law, they are instruments of choice.

When the razor of the state meets the hair of the believer, the result must not be obedience through fear—it must be respect through recognition.

The jurisprudence of the future must move from regulating how we look to understanding why we look that way.

And that journey—from appearance to awareness—is the next evolution of human rights.

Uganda’s Moral Mirror

If Eddie Mutwe’s humiliation becomes a landmark case, Uganda will be forced to answer its own moral question:

Can the state that claims to fear God continue to trim faith in the name of order?

If the courts rise to the occasion, they will elevate Uganda into the circle of civilised nations that treat religious appearance as a sacred expression.

If they don’t, then the law becomes just another razor—cutting where it should heal.

The Closing Benediction

The day Uganda acknowledges that a dreadlock can be a prayer, that a beard can be a belief, that hair can be holy—that day, our Constitution will stop speaking in ink and start breathing in spirit.

Until then, the Rastafarian, the Nazarite, the Sikh, and every man or woman of conviction will stand as living petitions, awaiting judgment not only from courts of law but also from the court of conscience.

Because when the state becomes the barber, liberty becomes the hair on the floor—and justice, the mirror that refuses to reflect the truth.

For the scissors that cut hair are not half as dangerous as the scissors that trim faith.

About the author

Arinaitwe Reagan is a Ugandan wordsmith, philosopher, and social activist. His existence is a testament to the transformative power of language, which he wields to challenge societal norms, spark meaningful conversations, and inspire positive change. A voracious reader and astute observer of human nature, Reagan's literary pursuits are informed by a deep-seated desire to understand the complexities of the human condition. His poetry and prose are infused with a sense of wonder, curiosity, and empathy, reflecting his commitment to exploring the intricacies of the human experience. As a passionate public speaker, Reagan has honed his ability to convey complex ideas with clarity, conviction, and charisma. His oratory skills are matched only by his capacity for active listening, which enables him to engage with diverse perspectives and foster inclusive dialogue. Through his writing, speaking, and activism, Reagan seeks to contribute to a more just, equitable, and compassionate world. His work is a testament to the enduring power of words to inspire, educate, and uplift humanity. He completed his primary level from St.Joseph's Preparartory School (2017)in greater Bushenyi in Western Uganda and later in 2018 he joined the most prestigious boys School in East Africa where he notably established himself as the class coucillor in 2019,moat informed student 2019,president Debate Club president Writer's Club,President Peace Club,as well as the school junior head prefect. He participated in Olympics Youth Camp in 2018 just as a young lad in form one,represented Uganda in Yale Young Africa's Scholar Program 2018,finalist in the Uganda World Bank Bank Debate Championship 2019,founding president Divine Mentorship Hub to train young breeds of leaders for Africa's next generation .He is a true Pan Africanist who participated in the Transformation Citizens Encyclopedia (TRACE),won National SESEMAT Science Competition 2022,awarded best studentt leader if the years 2019,2022 respectively, participated in the National Students Anti Corruption Challenge 2021,2022 respectively and Climate change dialogues as well as very many easy writing Competitions .He later joined CORNERSTONE LEADERSHIP ACADEMY-BOYS Ffor his A LEVEL Studies in 2023 where he was the school speaker ,president Debate Club,President Writer's club at school level and District level and was the president Executive Committee of Nakasongola District and National Level Secondary Scools Writers and Deabtors clubs respectively He served as the president of UGANDA NATIONAL STUDENTS ASSOCIATION (UNSA ) at District level as President DEC and national secretariat as 34th Secretary for Inter-School Affairs a role that mandated him to head all Secondary School students in the country. He featured in UNESCO documentary about literacy levels in Africa. Currently he volunters with Educate Uganda,Wananchi Youth Patriotic Forum, member of Africa Kwetu Studebts Association and agraduate of leadership and governance from KRUMBUKA LEADERSHIP SOLUTIONS in kigali Rwanda *land of a thousand hills*.Currently he is law scholar at ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY IN UGANDA. He believes it takes a revolution to create a solution